After wading through the Seoulite crowds with their iPhone screens blazing tiny future K-pop stars into the night, Dee and I hit up a convenient store for snacks and beer before settling onto a bench in one of the many hangout areas. There was something so relaxed about my newfound friend nearly half my age, with her unbelievably long hair tied up in a high, scrunchied ponytail, her oversized pink T-shirt tucked into her mom jeans, and her silver glitterbomb backpack shimmering like a disco ball in the open September air.

“How was your meeting at the adoption agency?” I asked.

“I didn’t find out much.” She cracked open a beer. “I just went in. Didn’t even schedule an appointment. Did you find out anything?”

“Yeah, they found my mom,” I said, as I offered her some chips. “She doesn’t want to meet me.”

We sat in silence as a small group of young Koreans began setting up a keyboard, mic, and speaker in the middle of the courtyard.

“You know,” Dee’s voice lingered, “it’s weird that I don’t see any gay people here—like openly gay people, because I have so many gay friends in NYC.” She took a swig. “Like all of my friends are gay… although, not a lot of lesbians,” she added, surprising herself, then continued, “but, like, my best friend is this Filipino gay boy, Brad.” She stopped in her mental tracks with another epiphany, “Actually, I think the only straight guy I know in New York is my boyfriend. Holy shit.”

“Actually, your boyfriend is totally gay,” I said in a tone bearing bad news. “He told me, like, right before we met up.”

“Aw, he’d be such a good gay boy too,” she swooned. “Seriously though, I mean do you notice that? That there’s like, no gay people here just, like, being gay or whatever?”

“Yeah, it’s super fucking weird because I see gay people all the time—mostly guys—but I know they can’t be out, and it’s creepy because they may not even know they’re gay. It’s like being in Arkansas or something. Except they’re all wearing make-up.”

“Gross, why would you be in Arkansas?”

“I’m kind of from there,” I half-explained, almost apologizing.

“Oh whoops… my bad,” she laughed, polishing off her beer. “But are there like any lesbians here or anything? Not to assume that you would know just because you are one,” she backtracked.

“I have no idea! I’ve actually been wanting to find a dyke club here just to see what the scene is like. It has to be crazy, right?”

“Oh my God, me too! But, like, I couldn’t because, you know, I don’t want to be ‘that straight girl.’”

“Well shit, you can just come with me. I don’t drink and you’re not gay, so together we’ll sort of belong there.” We laughed.

“Seriously though,” Dee’s tone lowered. “I’m totally cool if you need to ditch me and get laid or whatever.”

“Yeah, I doubt that will happen. I’m not so into Koreans.”

“Well, I’m just saying. Don’t pass that ass up on my account.”

*

My friend Simon had warned me that I would have trouble finding this popular fried chicken joint. “Reggae Chicken”—as it was aptly named—had a nondescript storefront, unlike the other surrounding eateries, which announced their presence with all the subtlety of a McDonald’s playground on fire. With a few chairs pushed up against the wall next to a door, propped open by a questionable stool, its entryway was like the yawning mouth of an urban cave, exuding all of the charm of a toothless free hug. And above it all, the words “GAE CHIC” poked out under the overgrowth of vines lounging on the roof, looking like the thick, sleepy dreads of a Rastafarian. Once inside, the warm glow of red lights replaced the waning rays of daylight fading against the crimson walls, and I quickly realized this place for what it was: a small Bob Marley-themed dive with the Jamaican flag and framed portraits of ganja crowding every surface available. The hostess led us to a table where I sat in an actual hole in the wall.

Seoul was disorienting, but I was amazed by how supremely effortless it felt to be racially integrated into a society, and I had been there for over a month. Every day the prospect of moving there grew more seductive with its cheap food, taxis, and Asian-fitting clothes. And Simon and I both loved Korea for its greatest attribute: everyone left us alone. No lingering looks, no one asking where you’re really from. It turned out that the freedom to simply exist lifted a crushing burden I never even knew I was carrying.

“Have you tried to date here?” I asked after our drinks arrived.

“Yeah, it’s a little weird,” Simon hemmed. “In Korea it’s great though. You get to feel like a man.”

I would frequently hear this refrain from male adoptees who had moved to Korea, that they had found an escape from the feminizing West. Their masculinity was never called into question here, even with a face full of K-pop make-up.

“I don’t know, Simon. I’ve been here for nearly a month now, and I’m pretty sure I’ve never once felt like a man,” I smiled.

“You know what I mean. The women here, they don’t look at you like you’re less.” He nursed his beer as I munched on our free popcorn.

“But we get those looks—that we’re less,” I crunched. “It’s just different and doesn’t come with emasculation.”

“Fair enough,” he conceded. “But girls here let you open doors for them. They’re not afraid to cook for you…”

I sensed that along with the Jamaican lager and the Bob Marley photos staring at us with blood-shot eyes, we were entering 1960s territory. So many male adoptees’ feelings of being “real men” conflated their masculinity with a kind of misogyny, the kind that ironically led to their mothers giving them away. Male adoptees could marry native Korean women, but the inverse was unthinkable. Noticing all the couples in the restaurant — women with all the sensibilities and physical attributes of a Korean Mad Men and men looking for a sex-doll mommy — I wondered if a giant metropolis like Seoul was still so gendered that even with the evaporation of race, I could ever be comfortable here in my own queer lady skin.

“So, then, what’s weird about dating?” I asked again.

He stiffened on his stool. “Korean women are too status-oriented. They want you to drive an expensive car and have a high-powered job.”

I grinned. “Right. That doesn’t sound emasculating at all.”

After demolishing our fried chicken, potato wedges, and onion rings, Simon walked me over to the nightclub area of Hongdae, where the dyke bar was to be found.

“Too bad you can’t stay for a drink,” I said, as we wandered the streets looking for the small alley that would lead us to Mong, the lesbian bar where I had planned to spend the evening with Dee.

“Yeah, I don’t think they let our kind in,” Simon smiled.

“Or maybe they do?” my voice wondered as we both noticed the hetero couples smoking outside. But as we approached, it became clear that they were in fact not straight at all, and that half of the women outside smoking shared Simon’s relief of feeling like a man in Korea. We laughed.

“Well, I guess I’ll leave you here to meet your friend,” Simon demurred. And with that he wandered off into the night.

I stepped through the glass doors into the trendy bar adorned with an entire wall studded like a darkly lit Twister board and suddenly remembered that I hated gay bars only slightly less than straight ones. It felt disorienting to be inside a bar at all, so to be in a gay bar on the other side of the world crossed over to surreal. I looked around at the few couples sitting at the dimly lit tables and booths and noted the K-pop crooning from the dark corners of the ceiling. It was utterly queer.

I took a seat at the bar, glanced at the menu, and instantly ordered, “Omija mojito, no alcohol.” While my drink was being mixed, I stepped outside for a smoke where a young, ravishing girl sat, saying something incomprehensible and motioning for a light.

“I don’t speak Korean,” I stated flatly as I lit her cigarette, trying not to stare. She appeared to have stepped straight out of the nineties, a Korean Audrey Horne from Twin Peaks, with her short, wavy hair, leggings, and silk top under a blazer with more shoulder pads than an episode of Lois & Clark. Maybe I am into Korean girls, I reconsidered as she exhaled a cloud of smoke under the cold flicker of electric blue lights. She stared knowingly at me, considering my presence while her cigarette, stained lipstick red on one end and burning scarlet on the other, dangled in her hand.

“How do you speak English so well?” she asked.

“How do you speak English so well?” I echoed.

“I teach English.” She spoke with a slight accent before breaking into the laugh that belongs to women who know they are beautiful.

Happy to be in a position to chat up a girl, I engaged her. “Where did you learn it?”

“I’ve taken it all my life in school,” she inhaled. “And a long time ago my parents moved to Brooklyn for one year. But I was very young. Nine years old.” Her eyes stayed fixed on me. “What is your name?”

“Mee Ok.”

“Mmm… You don’t hear that name much anymore.”

“You don’t hear it at all in the States.”

She smiled coyly. “You are American?”

“By nature, not by birth,” I nuanced, as I packed my bowl with tobacco.

“I like your pipe. We don’t have those here.” It was true. All of their tobacco shops were riding the vaporizer wave and selling candy-flavored cigarettes long outlawed in the West due to their appeal to children. “Can I see it?”

I handed it to her as she fingered it gently. “It’s a nice pipe.”

“It’s British,” I said out loud, immediately regretting it. It’s British, I mocked in my head. Good one.

She laughed as she handed it back to me. “What do you do in America?”

“I’m a writer—or trying to be,” I looked away, insecure. I wasn’t published anywhere, had just started a graduate program at the age of 37, and had, well, less than nothing going on before that.

“Ah, so you are writing a book?”

“That’s the idea,” I spoke quietly as I leaned in to light another cigarette.

“What is it about?” Her mouth, painted too red, seemed to shape the air as she formed her words.

“It’s about my life,” I recited, like an idiot. “People say it’s an interesting one.”

She gazed out at the quiet alley, hidden from the rows of night-food, bass beats, and throbbing bodies in the next street over. “My life is not so interesting.”

“Well, you are gay in a country that doesn’t approve of it,” I offered.

“Who doesn’t approve?” she asked, offended.

“I read that at Seoul’s gay pride two months ago there were more protesters than queers.”

“Oh that,” she waved the air, as if brushing away the ignorance.

“You don’t think being a queer person here is interesting?” I protested. “It’s so… taboo, I thought.” I was completely confused why she was so blasé about the whole thing. I thought of my first date in Korea with the 34-year-old professor who had suggested Mong to me a few nights before over text, though she had been too afraid to ever come here herself — or any gay bar in Korea.

“I just live my life. Queer, as you say,” she exhaled. “It’s no big deal.”

“Are you out to your parents?”

She dropped her cigarette on the pavement and stamped it out with her stiletto, her eyes growing wide and incredulous. “Of course.”

“Really? But that’s unusual… isn’t it?” I pressed.

“Hmmm…” she hummed as though she were falling asleep. “I like you. You seem like a writer.”

She then stood up and walked over to the door, expecting me to follow, which I did. We sat in the dark, sipping our drinks, when she suddenly hopped off her bar stool. “Someday I hope to read your book. I have to go now.” Then she strutted over to the entrance where a tall and dashing woman entered, as handsome as any K-pop star, and together they disappeared into the shadows of the bar while I faded back into obscurity.

Moments later Dee tapped me on the shoulder. “Shit, dude, sorry I’m so late. This place is a bitch to find.” She took a quick glance around. “It’s weird to try to find a place that sort of doesn’t exist, you know?” She set down her bag and looked up. “What are you drinking?”

*

After ordering her first round, Dee swung around to stare out into the darkness of the lounge. “Damn, this bar is tame. Not really a place to meet the ladies,” she observed, picking up that everyone in the room was in a couple. When the butch bartender came back with her martini, she asked, “Is there a dyke club that’s, like, a party?”

Shortly after, we followed the bartender’s directions, retracing our steps back and forth trying to find a place that made every effort to remain hidden. The streets themselves appeared as broken as the bartender’s English, with paths searching for something but leading nowhere, as if old confused cattle trails were recently paved over, uneven and strange, slicked by dystopian neon lights.

“It’s supposed to be, like, right here… right?” I asked, side-stepping the throngs of club-goers crowding the tight alleyways. We had circled this area several times already.

“Maybe it’s up there?” Dee pointed to the tallest building around.

“Hey, are you guys looking for Labris?” I asked a group of three queer southeast Asian women who looked lost and ready to party.

“Yeah, the map says we are here,” the smallest one said in an accent I didn’t recognize.

“Where you from?” I asked, raising my voice over the club music.

“Indonesia,” she said.

“Singapore,” said the others.

“Why are you in Seoul?” I asked.

“The gay scene,” they chorused, as if I were blind to Korea’s gay awesomeness. Suddenly, I understood. In Asia, this is as good as it gets.

“Let’s just go up there and see.” Dee turned and started marching toward a shadowy entrance while we sheepishly tried to keep up. Once we were all packed into the elevator, she punched the 8th floor, beaming us all up to God knows where.

When the doors rumbled opened, there was only black. A curtain that, once pulled, revealed a round woman with a buzz cut checking IDs not for age, but for sex. No men allowed. We got a stamp on our hands and a plastic token that was good for one drink and slid through yet another dark curtain, where we were instantly caught in slow-motion, frame by frame, blinking under strobe lights. A thick bass vibrated through a large warehouse space that opened before us—multiple stages, high industrial ceilings, a long bar with bartending ravers, and two DJs spinning high above the dance floor in a carved out, high tech cave. I took a deep breath. I am way too old for this shit.

It was packed and the music was so loud it was hard to remember that no one was supposed to know we were up here. Everyone smoked inside the hazy room due to elevator traffic and also because a collection of drunk dykes on the street would give away our position, inciting attacks from Korean men or inviting evangelical protesters. As we made our way to the room-length bar so Dee could get a drink, I played the fine-drawn game of surveying the room without making eye contact with anyone. Initially the warehouse looked like what I imagined a straight club in Korea would look like, everyone playing a strict gender role—long hair, dress, and make-up or slicked, shaggy men’s coiffure, hip hop outfits, and liquid eye-liner.

“God, I would’ve cleaned up if I had lived here in my twenties,” I thought out loud.

“Oh yeah? How so?” Dee asked, sipping her drink, the bright futuristic color of radioactivity.

I showed her a picture on my phone from before I got sick, looking rakish and bored in my tight jeans, Italian leather shoes, and a tailored suit jacket.

“You don’t think you could clean up now?” she asked.

“Korea’s totally Eurotrash,” I protested. “And I look like I’m perpetually on my way to an ayahuasca ceremony,” I added, noting my chakra T-shirt, moonstone necklace, and one pair of Lululemon pants, which I basically lived in.

Dee laughed through her drink. “It’s cool though. You got your own style. I mean, it’s not like I’m dressed for this place either.” Dee moved around the room so effortlessly, having no stakes in this game. I didn’t really either, but something old had risen out of me, the fierce yet tender rumblings of a dormant libido in a space meant to incite sex. “Are you sure there aren’t any guys in here? Because like, I don’t want to be a dick or anything, but I see a lot of dudes.”

“Yeah um… they’re not dudes,” I laughed, thinking of all the times my ex-girlfriends and I were asked who “the man” in the relationship was.

“Are you sure?” she asked, unconvinced but respectful of my gay authority.

I looked up. “The only actual guys in here are those two shitty DJs.” The music was objectionable on a number of levels. Generic techno reprisals that were impossible to dance to spun by men in an otherwise all-female space. “This music sucks even for the kind of music that it is.”

“You don’t like techno?” she asked, surprised.

“Not this.”

She paused and listened. “Wow, yeah, okay. I mean, dude, how many times can you drop a beat?” Dee continued to sip and scan the room. “Okay, over there, with the white T-shirt. That’s not a guy?”

I followed her gaze across the room to a handsome young woman in what appeared to be full male Korean drag, while Simon’s voice rang in my ears. In Korea it’s great. You get to feel like a man. “Yeah nope. That’s a woman.”

“Fuck!” Dee yelled, frustrated and embarrassed. “Okay, but definitely the one standing next to her, right?”

“Also a woman,” I laughed.

“Jesus Christ, what the fuck is wrong with me? Am I just, like, too straight?” she stared at the two women as if they were the riddle of the gay sphinx. Then I watched the answer dawn on her, a look of disappointment passing over her face as she whispered, “Yeah, I’m just too fucking straight.”

“If it makes you feel any better, I’m really fucking gay,” I encouraged. “I’m probably even gayer than you are straight. Like, I have zero interest in going to a straight club with you and I have, like, a straight friend—and he was a theater major.”

“Yeah, I feel you,” her spirits started to lift. “But how can you tell?”

“Honestly, one easy trick is the shoulders. Look at the DJs’ shoulders.” We scrutinized the area above the stage. “Now look at your girl’s over there.”

“Oh shit,” she glanced back and forth. “That’s a pretty awesome gender hack.” Then someone else caught her eye. “But what about h—them.” She was staring at a butch rugby-looking Korean with the shoulders of a well-fed ox.

“Look at the chest,” I hinted, like a really fucked up Mr Rogers. “It’s harder too because, honestly, Asian men and women kind of look the same. Like the fishiest drag queens are always those bitches from Thailand, you know?”

“Wooooow.” The second drink was starting to hit her. “That’s so true.”

“Do you want my drink pass? I’m not going to use it.”

“Are you sure? I mean, maybe you want to buy some girl in here a drink,” she said.

I surveyed the room pulsing with rainbows of light, a cotton candy cloud of smoke gathering above the dance floor as drunk girls on stage let it all hang out because it was the only place they could. It was another world from me, far away from the girl I had imagined I was chatting up just an hour ago, and even further from the one where my birthmother would ever want to meet me. In this world, the one that I actually found myself in, I realized I had already retired any thoughts of taking a chance on yet another Korean woman.

“Nah,” I passed Dee the token. “I’m good.”

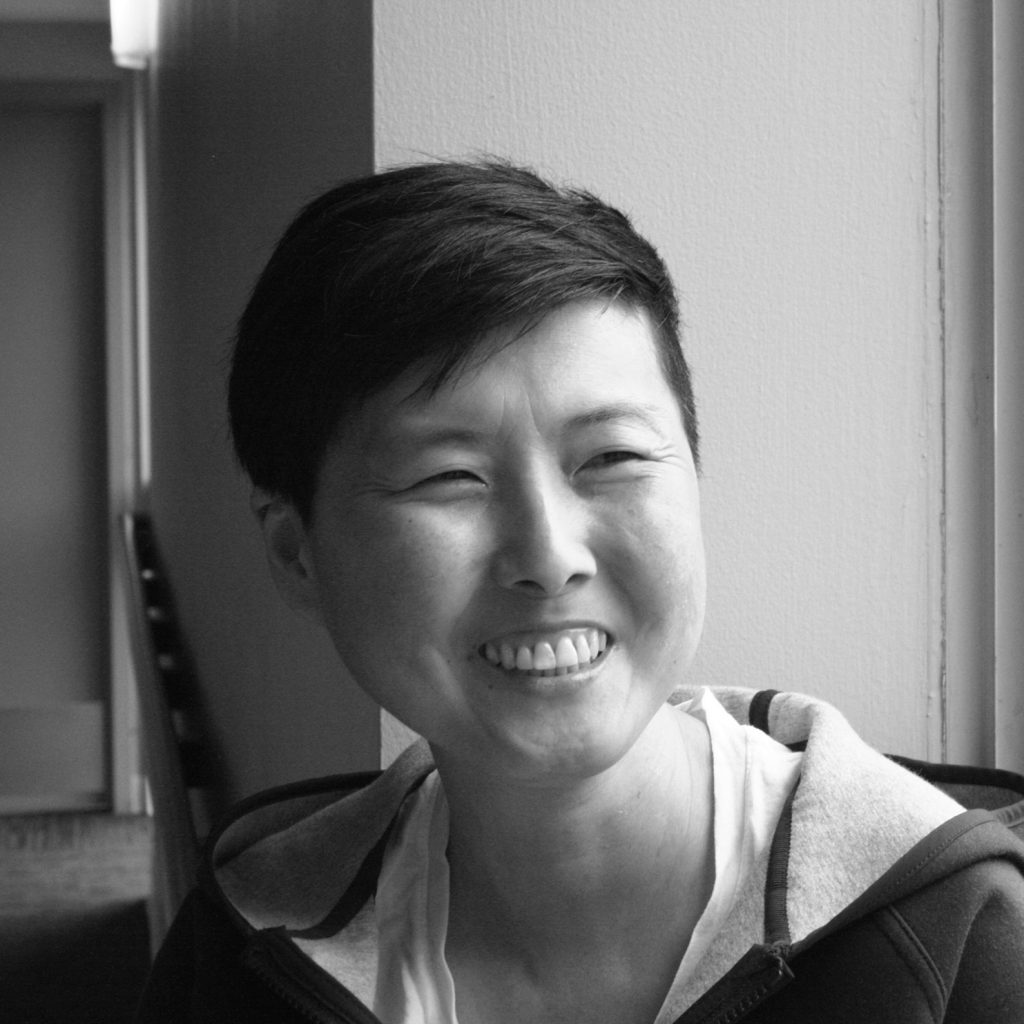

Mee Ok Icaro is an award-winning essayist, poet, and memoirist. She placed as runner-up in the Prairie Schooner Creative Nonfiction Contest and was a finalist for the Scott Merrill Award for poetry as well as the Annie Dillard Award for Creative Nonfiction. Her writing has appeared, or is forthcoming, in the LA Times, Boston Globe Magazine, River Teeth, Bennington Review, Cincinnati Review, American Journal of Poetry, Michael Pollan’s “Trips Worth Telling” anthology, and elsewhere. She is also featured in [Un]Well on Netflix. More at Mee-ok.com.