A young man sang in wild tones

from isolation, in operatic moans

that filled the cathedral ceilings

of bedlam, vocalized feelings:

“I’m bored. I’m bored.

I’m really fucking bored.”

Over. And over. And over.

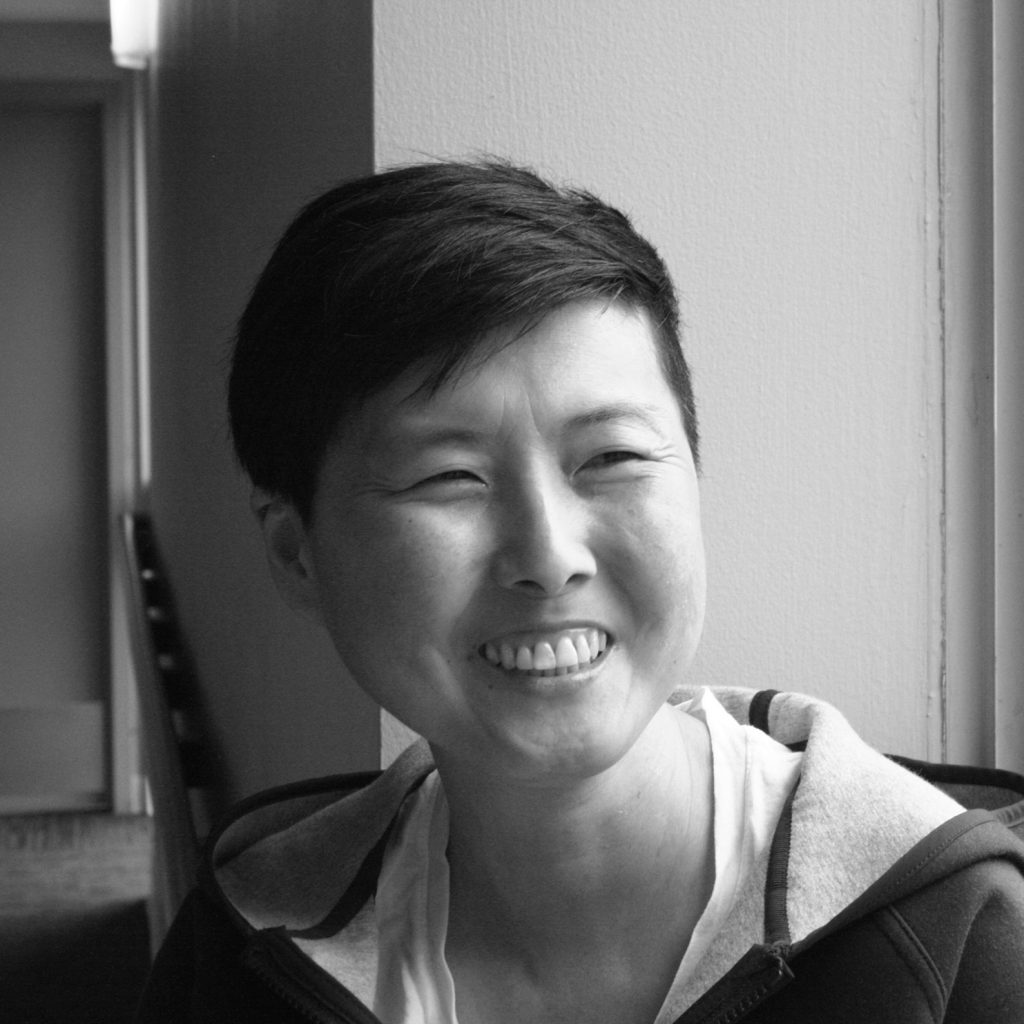

John Quintero was a former member of the workshop before being transferred to another facility. Highly intelligent, he writes sonnets that can be stunning. A polymath, he is able to discuss almost any topic and listen deeply.