“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.”

—W.E.B. DuBois

Tamir Rice was shot twice within seconds of two cleveland police officers arriving on the scene. He was 12 years old, brandishing an airsoft gun, and guilty of playing while black. He died the following day from the gunshot wounds—a homicide. A little over a year later, an ohio grand jury decided not to indict the two men who murdered Rice, a boy.

About five years prior, my friend, Chris—whiter than the whitewashed u.s. history books (1) we read in high school—ran around our suburban neighborhood brandishing an airsoft gun, hollering our names or some shit. We were about 14 or 15 years old, freshmen, and involved in a painful, real-world crossover of tag and Call of Duty. Most of us kept the game indoors and in backyards, but Chris took the game to the streets. He wanted to give us a scare, and so he rode up on his bike, dropped it hastily on the curb, ran up to the doorstep of another friend, Justin, and pounded away at the door—gun at his side with its orange tip painted over so that it appeared real. He yelled for us, Justin and I, but no one answered; we were out riding bikes around the neighborhood.

When we returned, Justin’s mother chastised us both, “I was about to call the cops on your dumbass friend!”

Motherfucker tried to run up on us and almost landed his white ass in jail (2).

Years later, watching Samaria Rice mourn the loss of her “happy boy,” I wondered how long I’d’ve lasted if the roles were reversed and if I, in my brown skin, set out that afternoon with a toy gun painted black.

*

america’s problem has always been the color line. It slashes long and red through our history as if carved by a sword, and it bleeds steadily over every growing limb of the nation’s body. Applying more pressure to the tourniquet has neither healed the wound nor stopped the bleeding but sometimes causes the vein to rupture. “It was a phase of [the color line] problem,” DuBois elaborates on his oft-quoted prophesy, “that caused the Civil War.” There have been many such phases.

Perhaps the color line is nowhere more visible than in our schools and neighborhoods. My parents met in the not quite urban, not quite rural waco (3), texas during the reign of reagan. His administration declared a war on drugs. Decades later, an aide to president nixon would admit to conceiving of a war on drugs as a potential war on blacks and black neighborhoods (4) around the time my parents are born in 1970.

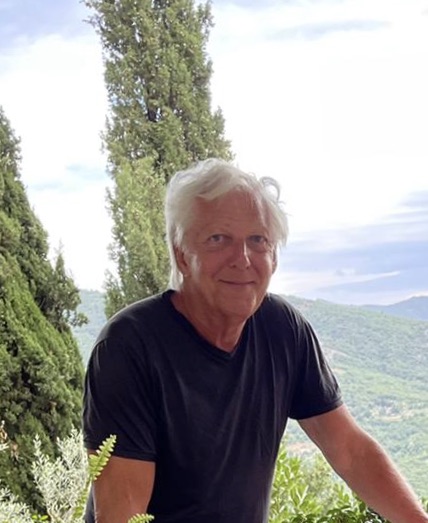

My mom and my dad met in high school—high school sweethearts, as it goes. Though they came from drastically different neighborhoods, they were districted to the same of waco’s two high schools. The (re)segregation of america had to be slow and coded. She was a popular kid from the poor, black side of town who wrote poetry and dated black boys mostly, and he was the quiet, stammering white boy who admired her from afar. A nerd, she’d tell us, their kids, many years down the line, a straight up nerd. He liked hip hop and sports as did the popular boys, but he liked them in uncool ways. He would explain that Public Enemy had sampled The Isley Brothers on “Fight the Power” while everyone else just nodded along to the beat, and he could cite you Nolan Ryan’s rookie ERA even if, especially if, you hadn’t asked.

Perhaps, it’s best we don’t know what attracts two people to each other, particularly if it’s your parents, and let the relationship speak for itself instead. The attraction, we explain away with animal magnetism, some immutable force between certain bodies and certain souls—the birds and the bees, cats and dogs, opposite poles on a magnet, other such things.

Listen, I don’t know what possessed my whiteass father to finally work up the courage to ask my mother to prom, but I know that he did and that she initially laughed until she realized that he was serious and thought—Why not?—and told him where to pick her up. Their picture from that night screams 80s, back-dropped by a sparkling blue velvet curtain and pastel pink balloons rising on both sides of them, as this mismatched pair—black and white against the colorful background—stares ahead smiling, proof of a fun night against all odds.

They married in 1990 (5). A year later, Rodney King is beaten by los angeles police officers and the assault is caught on tape. los angeles erupts. A year after that, in ’92, I am born and then, my twin sisters, Ashley and Adrienne, follow two years later. In the years since, many such assaults are caught on tape; many cities erupt. The color line burns for all to see.

*

My parents (de)segregated my sisters and me a month or so after 9/11. They wanted us to go to “better schools,” I’ve been told, though our family could barely afford the move and would later foreclose on the suburban home meant to spare us a bad education. I was turning 10 years old; my sisters had just turned 9. All three of us watched the towers fall from our classrooms as did most of our classmates, cause couldn’t nobody’s parents come pull their kid from school on a Tuesday—national tragedy be damned. When we moved from Dallas ISD (5.6% white in 2019-20) to Wylie ISD (47.7% percent white), I learned that this was not the case everywhere. Our 7th grade history teacher had us chronicle our memories of 9/11 for a personal time capsule (6), and according to their narratives, many of my new classmates went home that day and huddled up with white collar parents given the afternoon off.

Ruby Bridges was only 6 years old when, on November 14th, 1960 (7), she became the first black child to attend a white school in the roiling hotbed of racism that was the south. Rioting white men and women, grown adults, scream and shout and blockade the doors of William Frantz Elementary in new orleans, louisiana. Her moment in history is now forever ingrained in the american consciousness both as a photograph and a painting. In the photograph, she is led hand-in-hand by her mother while towering, suited, white u.s. marshals trail behind them, warding off a crowd of angry white fists hurling spit and slurs and trying to keep her from entering the school. Bridges’ mother’s eyes are closed in the photo, though she stands tall and faces ever-forward as her daughter hides behind her thigh. In the photo, the mother, not Bridges, appears the focal point—her red shirt centered in the frame drawing the eye to her poise as the mob threatens to consume her daughter at the precipice of her new school. Norman Rockwell’s famous depiction, “The Problem We All Live With,” removes Bridges’ mother, however, and finds Ruby alone, dwarfed by those towering, suited marshals—black in Rockwell’s vision with clinched fists—whose heads stretch beyond the painting’s frame. Behind her the word “nigger” is painted in black letters, a splattered tomato runs blood red down the wall, but Bridges looks resolutely forward.

In middle school, I wanted so badly to call my friends my niggas, as I was then getting into hip hop, but all my niggas was white. Niggas (8) was cool; niggas meant blood, meant kin, meant comrades. I longed for that bond, but all my niggas was white and I couldn’t abide by any white folks getting the idea that nigga belonged to them again. The word soured years later when a skinhead walked into the Starbucks my mom managed and brandished the slur. I was waiting dutifully in a booth for her to clock out and take us home, reading comics with my bulky iPod tuned to an Outkast song when the skinhead orders a Venti something with an Italian name, tripping over the syllables in his thick country accent, “Can I get a Venti Mah-Chee-Ah-Ta?” When they call his name, “Macchiato for Earl,” and after he takes a sip, he brings the drink back to the counter, back to the black woman who took his order, and tells her it tastes like piss. “I knew I shouldn’t have trusted a nigger with my coffee,” and he pours the drink onto the floor and the black woman will have to clean it while her son watches from a table nearby.

Sounds like the premise to a groan-inducing dad joke, the type my white grandfather loved to tell. “So, a skinhead walks into a coffee shop…”

I knew the skinhead’s son—the boy with a confederate flag patched prominently onto his backpack, the boy who cried heritage whenever the teachers asked him to remove the symbol, the boy who claimed that I “talked white.”

That same day, my mom adopted a black cat from a pet adoption she hosted at her Starbucks. During the long, hot day– the kind of day when you can’t distinguish your sweat from the humidity– the cat coiled up on my mom’s lap and purred softly, perhaps an instinctive impulse to comfort the wounded. My mom, living proof that cat ladies aren’t always single, was smitten. The cat is slender, with thinning hair around the eyes, but still warm to the touch. My sisters fell in love too and warded off any potential adoptees until the end of the day when they could take the cat home. Later, we learned the black cat, Ebony, had worms, eating her alive from the inside. My mom was too proud to talk about the worms gnawing at her insides and wouldn’t address the incident except to say that all customers are assholes but some are fucking assholes and those are the only distinctions, but she complained often about the ache in her knees and it was hard, then, not to picture her kneeled and cleaning up the mess someone else has made.

One day, I asked the skinhead’s son what he thought that confederate symbol meant to me. We rode the same bus and I stared at that rebel flag most mornings and I wanted to bait him into calling me that curse his father affixed to my mother, but he stammered and walked off. He kept his racist patch throughout high school. It didn’t matter anyway; the symbol was plastered all over the pickup truck bumpers parked in the concrete valley that stretched from the back of our school to the cavernous football stadium.

Fifty years after entering the history books, Ruby Bridges penned an essay proclaiming, “I’m still trying to integrate my school.” Her foundation was preparing to break ground on a project to refurbish William Frantz Elementary, following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. Three years later, the building reopened as a public enrollment charter school, Akili Academy, which integrates Bridge’s story into its everyday curriculum and preserves her classroom for special programs—the problem they all contend with.

*

Dajerria Becton, 15 years old, laid prostrate as though dead. A burly white office kneeled upon her back (9). Her friends watched, filmed, pleaded with the officer. All except for the officer were clad in swimsuits—their dark black skin exposed in the summer sun. They had thrown a pool party in an upscale neighborhood in mckinney, tx (10), and though the organizer lived in the neighborhood, her friends did not. Police were called.

Dajerria is subdued a year after Tamir Rice and Michael Brown are murdered, three years after Trayvon Martin. Anyone watching the video would be justified in speculating a grim ending for Becton too, but gratefully, she walked away alive and instead became a litmus test for the issue of race in that contentious historical moment. white conservative viewers saw a teenager who got the consequence she deserved for infiltrating a nice neighborhood and throwing an unsanctioned pool party. The officer simply performed his job despite the teenage mob ignoring his commands and filming him all the while. Black and brown viewers saw yet another kid guilty of being black in the wrong space and an officer who capitalized on the moment to an exercise the violence inherent in power.

My sisters and I spent summers in a suburb of phoenix, az with our grandparents. They enrolled us in a swim team. Thank god arizona is burn-the-soles-of-your-shoes-off hot because even its small towns have community pools. Not very many remain in texas where Dajerria Becton was assaulted. Community pools closed in favor of neighborhood pools behind stone fences, requiring key cards for access. Our wylie neighborhood had such a pool. We moved several times in that same neighborhood—once after foreclosure, twice after eviction—new keycards issued each time and lost just as frequently. Instead, we got by on the kindness of neighbors who would recognize us and grant us passage.

“Do y’all live here?” we heard on many occasions.

My sister, Ashley, was a natural swimmer. She placed first in just about every one of our swim meets, but moving a lot has a way of losing such accolades and her medals and ribbons are either in a box or lost to the void. Adrienne and I had our moments of modest success in the water, but there’s no love lost in losing a bunch of third place ribbons and bronze medals. Still, all three of us took to the water like fish longing for the sea.

“I thought black people can’t swim,” friends of mine have said. All of ‘em white.

“We can,” I usually say back. My mom can’t though. Her neighborhood ain’t had any kinda pool, and the neighborhoods with pools, generally, don’t grant access to black people. In an Atlantic retrospective on the mckinney pool incident, Olga Khazan writes of a “council (11) candidate in wylie, which is not far from mckinney, who promised not to approve affordable-housing developments in the city.” They ain’t got pools in Section 8 housing.

And they ain’t got Section 8 housing in the burbs. We snuck in past the redlining; we learned to swim, though I admit I watched my back for fear of knees waiting to press us out.

*

Before divorcing after twenty-five years of marriage, my parents’ household would tally two children, thirteen cats, and three dogs. My dad claimed one dog, and my mom, the remaining fifteen animals. When I tell you that I was raised by cats, I do not mean figuratively. I mean that it’s hard to make sense of a childhood with that much fur and litter, always altering the atmosphere of every memory, especially with how often we moved—were forced to move—fur and litter providing the other few constants besides the family, itself. I mean that I can’t tell you the plethora of pets was what eventually split up my parents, but that I have my suspicions. As with all tensions, we can trace only their manifestations, not their cause.

In 1990, when my parents married, Sheryl Gay Stolberg of the New York Times reports that “63 percent of nonblack adults said [in response to a University of Chicago’s General Social Survey] they would be very or somewhat opposed to a close relative marrying a black person.” Twenty-five years later, that number drops to 14 percent. My parents, always bucking the trend. Stolberg attributes these trends to a more famous black wife and white husband, the Lovings. No author but that of reality could’ve given them a more fitting name.

If you track it from their landmark court win, Mildred and Richard Loving were only legally married for eight years when Richard died in a car crash in 1975 or seventeen years if you track it from when they were arrested for marrying illegally in their home state of virginia. The “matriarch to thousands of mixed couples now sprinkled in every city (12)” never remarried. All she wanted was to return to their marital home in virginia after being exiled to washington and so she wrote then-attorney general, Robert Kennedy, and so he set her up with the ACLU and so they sued and lost and so they appealed and won at that highest of courts and so they returned to virginia where they both would die, thirty-three years apart, leaving behind three children, a farm, two dogs, and the ever-increasing normalcy for interracial couples to wed and part and love however they so please in this country where all men (13) are created equal.

Colloquially, america is a melting pot, but maybe a better metaphor is a house of thirteen cats. I’m talkin’ bout the purring, the smashing of vases knocked clean from the countertops, the frantic digging of litter, the frenzied scratching of carpet and furniture, the bickering of people who’d rather blame the animals in the zoo than their keepers, u know what I’m sayin’?

I’m saying, all my niggas was, actually, cats. I learned from them how to remain aloof when the house came crashing down. My sisters had each other—shared a room, built elaborate worlds with their stuffed animals and dolls and while I was occasionally invited to play along, I grew into social conventions that said I shouldn’t. Friends were rarely permitted over if the house smelt too much like cats which, you can guess, it always smelled like cats, and so those that could come over, friends deemed close enough to be family, had to understand that they were now one of the cats whether they liked it or not. When Chris came over, he would chase the cats, shooting them with rubber bands and giggling. Justin coined a jingle for one of the thirteen cats, Pumpkin, and he would sing it whenever she trotted by. Neither of them liked when the cats hopped in their laps but were powerless to stop them. They were outnumbered on our terf.

america ain’t no melting pot; it’s a house riddled with cats. DNA evidence suggests that cats domesticated themselves, kept their feral instincts all these generations removed, but still chose a life where food and shelter were readily available. The (re)segregation of america was just as inevitable. The laws changed, but white folks never stopped believing their shelter was a little alcove away from everyone else and so they crept out slow but steady and drew a line behind them as they fled, u know what I’m sayin? Race ain’t what broke up my parents; life did that shit. I’m sayin’ the cats needed a new home, I’m sayin’ sometimes it be nice when we let nature run its course—like one couple’s desire for home dissolving a domestic color line—and other times the house is left empty except for those staring forever out its windows.

*

Michael Brown was murdered for either petty theft or buying pot. Either way, his bloody body lied on the hot, missouri pavement for four hours before he could be laid to rest. He was 18 years old; he had just graduated high school.

In a small comic shop with narrow walkways with every space filled with comic book icons, captain america, himself, likely had his watchful gaze on me. I knocked over a display of Magic the Gathering Cards. A pack, apparently, had been ripped open and cards spilled all across the aisle. I hastily remade the display, stuffing the fallen cars back into their open package as best as I could. My friends, Justin and Chris, stood nearby laughing at me. When I had finished, we made our way to the exit, but the shop owner trapped us down one of the narrow walkways. He was a stout, bald, white man who didn’t have to try to look intimidating to three teenage boys. His dome shined beneath the fluorescent lighting as he directed his eyes down into mine. “Empty your pockets,” he told me. “I know you stole those cards.”

I refused; I hadn’t stolen anything, but he said he’d been watching me the whole time. “You looked very suspicious,” he said.

“I don’t even play Magic, man,” I said in my defense. He never accused or even looked at my two white friends, however, who both played the card game, but I stopped short of accusing him of racial profiling. I could see that weren’t no other niggas present that afternoon.

Still, I’m never quite sure how people see me. Once, attending a Radiohead concert, the only other black folks in attendance were selling bootleg t-shirts in the parking lot. This was pointed out to me by a white man, also selling bootleg t-shirts who looked at my off-black, off-white skin and thought it safe to confide in me, “I’m trying to make a buck out here but it’s hard with all these niggers around.” I stayed silent and bought a shirt. They were much cheaper. That day in the comic shop, I didn’t say much either. My friends and I eventually left in a huff, shoving past him, my pockets unemptied. “Don’t come back” echoed behind me.

“What’d you steal?” Chris later asked.

As with Trayvon Martin, as with Eric Garner, as with Alton Sterling, as with Walter Scott, as with all our kin whose deaths were made public, white conservative outlets searched for the reason Brown was murdered—the cardinal sin that justified that most heinous of them.

No one sought the sin of the officer, the murderer. And in the end, his sin was stricken from the record—no charge sought. As with Trayvon, the murderer walked free, the law at their side, injustice served.

I went to church the day after Trayvon’s murderer was exonerated. My church niggas was predominately white too. “I’m glad the jury didn’t give into the media hysteria,” I heard someone say, and so I knew I mourned alone.

My mom no longer went to church by then. “I got Jesus in the living room,” she’d say, and damn, that must have been one of helluva a church. I didn’t go to church much when Michael Brown’s killer walked—no charge for the shooting—four hours the body remained, bleeding—no charges pressed, not one—and still I wanted that bastard in hell.

I wanted that community indicted too for putting Brown before the bullet, and I wondered what his life might’ve been if the public money that bought his murderer a gun went into improving his school instead.

Like many black teenagers, Brown attended a segregated school (14), Normandy High School, with a 97% minority enrollment and 99% of which are economically disadvantaged. Two years prior to Brown’s murder, the school lost its accreditation and was under the control of the state. Students were forced to transfer, teachers were forced to reapply for their jobs, and the school was dangerously close to shuttering its doors. Much was made of this fact in the wake of Brown’s death.

Had Brown gone to a better school would he have been spared the bullet? The answer seems both obvious and not. That would require him to live in a different neighborhood in a different city (15) in a different state (16) in a different country altogether.

*

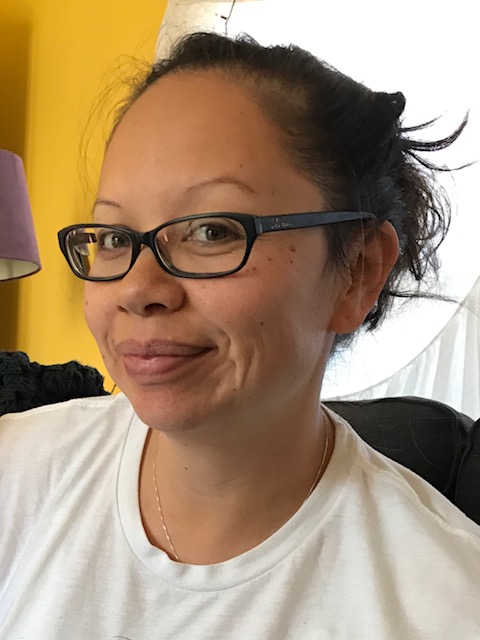

Barack Obama was chastised by conservative media outlets for remarking that if he had a son, he would’ve looked like Trayvon Martin. Let me say then that I have a mom whose smile reminds me of Sandra Bland’s.

It’s hard not to draw ourselves into these public reckonings with black mortality, hard not take it personally, hard not worry for our loved ones and for ourselves when we know the eye of the oppressor is ever vigilant. Because we were learned in the schools they gave us or else, like me, infiltrated the schools they hid in plain sight. Either way, we learned the lie of safety. It’s our moms that had to tell us not to stay out to late, to always do as they tell you, to put your hands up in the hopes that they don’t fire anyway.

I mean to say that I grew up on both sides of the color line, but because that color line resides within me, I will always see Sandra Bland’s smile as my mom’s and that it’s not supposed to be the son that worries for the parent but there’s a fatal, contagious disease spreading as I write this and it disproportionately infects our side of the color line because while my mom was an A student, she wound up an essential worker like many a body with her complexion cause that’s the way the system draws the path. I mean to say that if COVID don’t get her, it could be the bastard that pulls her over for failing to signal. A disease either way—of the body or of the body’s country.

I mean that when I see the smug, white face of kyle rittenhouse—the wannabe cop who murdered two demonstrators at a protest in response to the senseless shooting of Jacob Blake (17)—with his illegally-obtained rifle driven across state lines to protect other people’s property, I see Chris with that damn airsoft gun with the painted tip and I think of all the black bodies that have died for less and I wonder what it would take to be so free in this supposed land of the free. Free to terrorize. Free to make mistakes and live to tell the tale. Free to kill and walk away with hands up, exonerated before any trial, and go home and go to sleep and know the country belongs to you and always will.

Every time a murderous cop is set free, which is every time a cop murders, I see the color line that draws its way from segregated schools straight to segregated prisons and perhaps I should feel grateful that my parent put me in a school with a pipeline to a liberal arts college and not to the penitentiary but what I feel is guilty because what have I sacrificed that wasn’t theirs. Perhaps, the slow generational slog along the color line is the best we can dream for.

DuBois also preached that the talented tenth would elevate the race, but lord help me, I can’t buy into that fallacy either cause if we all ain’t allowed on the boat then let that ship sink. There ain’t no talented tenth—just a few granted a few more privileges than the rest. And even that olive branch is made of plastic. See, Lebron James—King James to some, “shut up and dribble” to one conservative pundit (18), and a “nigger” to one graffiti artist who defaced his home during the NBA Finals (19). See, black scholar, historian, literary critic, and Harvard professor, Henry Louis Gates Jr., arrested for trying to enter his own home (20). See, I went to a white school, and in the wake of protests over the murder of George Floyd, an old high school English teacher of mine shared a tweet demeaning black protestors as “subhuman animals.” Former classmates defended the hate speech as “conservative” values—”she’s just an old southern lady! What do you expect?” The south came back to claim to its own. “Niggas ain’t worth shit,” the tweet concluded. “BASTARDS.” Her twitter account includes the school’s acronym, WHS, and her profile pic smiles white above it all.

Where is the end of this sputtering tape, of this film reel stuck and spooling to create the illusion of movement, a simulation of progression? The line continues and continues to present a problem. 1955, two men dragged Emmett Till from his home, mutilated and shot him, and dumped him in a river. They said Till, 14 years old, whistled at a white woman, and for that they lynched him. 1969, fourteen militarized police raided Fred Hampton’s home and shot it to pieces. They said it was a “war on gangs,” they said the men in Hampton’s building were “violent” and “vicious,” and for that they shot him point blank while he slept and dragged his body bleeding through his own doorstep. 2020, three officers entered Breonna Taylor’s home, no-knock no-notice, and shot her 8 times until dead. They’ve tried since to paint her as caught up in some criminal underworld and not as the woman planning to serve as an E.M.T., someone planning to heal others.

Where is the end of the line? The line continues; we’ve deputized the lynchers. Bought they guns with school money. The house been on fire, and now, some white friends are acknowledging that, yes, the drapes are smoking maybe, and I’m thinking how it all seems so many years too late and wondering if it would be better to just let it all come burning down. But those white friends ain’t ever been my niggas. Ain’t none of their mommas ever looked like Sandra Bland. Still, I carry this charge that we might still be comrades, be kin, be blood, and maybe that’s from that white schooling (21), but those that defund black schools would defund white schools too if they thought them too radical—such is the preservation of power, the continuation of the line. Power sniffs out the oppressed and presses harder against their backs for fear of retaliation, and if we gonna push back, then something more than white comfort gotta give. Cause here we are at another phase of the color line, another rupture in a vein lined with gashes, and goddamn! it’s hard to walk straight or stand tall with so much blood lost, and so maybe we ought to give into the stumble and fall and blot the line with ash and dirt, blot it on real real thick, black as black can be.

1 Of the-Civil-War-was-fought-over-states’-rights variety

2 Pardon my slip. Normally, I’m an adept code switcher, but this one’s got me feeling different.

3 Known outside of texas as the site of the raid on david koresh’s compound and the home of gentrifying cuties, chip and jo gaines. Known in texas for just being a shitty town on the way to austin. However, it made statewide news when local skinhead, motorcycle gangs got into a shootout at a breastaurant called, twin peaks (think: hooters but with a somehow worse pun for a name).

4 “You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.” –john ehrlichman, former nixon adviser, in an interview with Harper’s Magazine published in their April 2016 issue.

5 Not until 1967, three years before my parents were born, did the u.s. supreme court knock down the interracial marriage bans in 16 states, including texas, with the Loving v. virginia case.

6 We were living documents of history, she proclaimed of us. I found it an overstatement until I became a teacher myself and saw those smoking New York towers in a textbook. “Wow,” a student of mine born years after the towers fell, “that must’ve been a scary time.” The irony was not lost on me.

7 Almost 64 years to the date, Tamir Rice is shot twice and murdered on November 22nd, 2014.

8 Ain’t no better discussion on the history and etymology on the word “nigga” than these lines from Q-Tip’s verse on “Sucka Nigga” by A Tribe Called Quest,

See, nigga first was used back in the Deep South

Falling out between the dome of the white man’s mouth

It means that we will never grow, you know the word dummy

Upper niggas in the community think it’s crummy

But I don’t, neither does the youth cause we em-

Brace adversity it goes right with the race

And being that we use it as a term of endearment

Niggas start to bug, to the dome is where the fear went

Now the little shorties say it all of the time

And a whole bunch of niggas throw the word in they rhyme

Yo I start to flinch, as I try not to say it

But my lips is like the oowop as I start to spray it,

so pack it up and go home, linguists.

9 Five years later, this maneuver will kill George Floyd, 46 years old, who calls out to his mother in his final recorded breaths.

10 A suburb 18 miles north of wylie, tx.

11 In high school, I briefly covered the city council meetings in the neighboring burb of murphy, tx. The meetings were largely boring save of any time taxes were on the agenda or businesses that might attract “undesirables.”

12 So labelled by the Associated Press in one of her few interviews, conducted on the 40th anniversary of the Loving v. virginia case. Mildred, however, credits the decision to “God’s work” and not herself.

13 Language, of course, borrowed directly from the u.s. constitution.

14 This in 2014 and not 1960.

15 st. louis, the larger metropolitan area of ferguson where Brown lived, is drawn over with many lines, all of them indicative of racial divides. The city has a long history of slaveholding. It was the site of the infamous Dred Scott case in which Dred tried to fight for his freedom in court and lost, and was a popular destination when many black people fled north following the Civil War. st. louis’ white communities feared what such an influx of blacks might do and thus forced these “slum” neighborhoods to the outskirts. Such districting persists to this day through infrastructure, evictions, and racially imbalanced municipal governments.

16 missouri was admitted into the union as a slave state in 1820 provided maine was admitted as a free state. You might remember this from way back when as the missouri compromise.

17 Blake was shot at seven times in the back while entering his vehicle (his three children inside) on August 23rd, 2020. Reportedly, Blake was breaking up a fight when cops arrived on the scene about a domestic disturbance. While the shooting, gratefully, did not kill him, it is unlikely that he’ll ever walk again.

18 The journalist, you see, didn’t believe someone like James should be discussing politics—this after he made some remarks about racism in america after his home had been vandalized with a racial slur.

19 “Being black in america is tough,” remarked James, even for the King apparently. It should be noted that Lebron’s home is in brentwood, a predominately white and affluent neighborhood.

20 He spent four hours in prison for his “loud and tumultuous behavior” while being arrested on his own doorstep.

21 More likely, it’s from my own black schooling, listening to Marxists like the assassinated Fred Hampton who believed increased class consciousness was the key to revolution for the black race. In his speech, “It’s a class struggle, Goddamnit!,” delivered just a month before his assassination, he asserts, “anybody else that has ever said or knew or practiced anything about revolution, always said that revolution is a class struggle. It was one class–the oppressed–those other class–the oppressor. And it’s got to be a universal fact. Those that don’t admit to that are those that don’t want to get involved in a revolution, because they know that as long as they’re dealing with a race thing, they’ll never be involved in a revolution.”

Sean Enfield is a writer and educator from Dallas, Texas. He received his MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks where he served as the Editor-in-Chief of Permafrost Magazine. He now serves as an assistant nonfiction editor at Terrain.org. His own work has been published in or is forthcoming from Hayden’s Ferry, Tahoma Literary Review, Terrain, and The Rumpus, among others, and he was the 2020 recipient of Fourth Genre’s Steinberg Memorial Essay Prize. Currently, Sean tends to a community garden in the golden heart of Alaska as an extension of the Bread Line, Inc’s anti-hunger programs. His work can be found at seanenfield.com.