Witness Weekends are Back!

Join us for readings from our Fall/Winter Issue contributors, all month long on our YouTube Channel and social media pages.

Join us for readings from our Fall/Winter Issue contributors, all month long on our YouTube Channel and social media pages.

Come join our *Witness* team! We are currently looking for volunteer readers, in every genre. For consideration, please send a short bio &/or CV, as well as your preferred genre(s) to witness.community@unlv.edu by Sept 25th. We can hardly wait!#writingcommunity #litmag #readers pic.twitter.com/mxHg2zxhiC

— Witness Magazine (@witnessmag) September 21, 2020

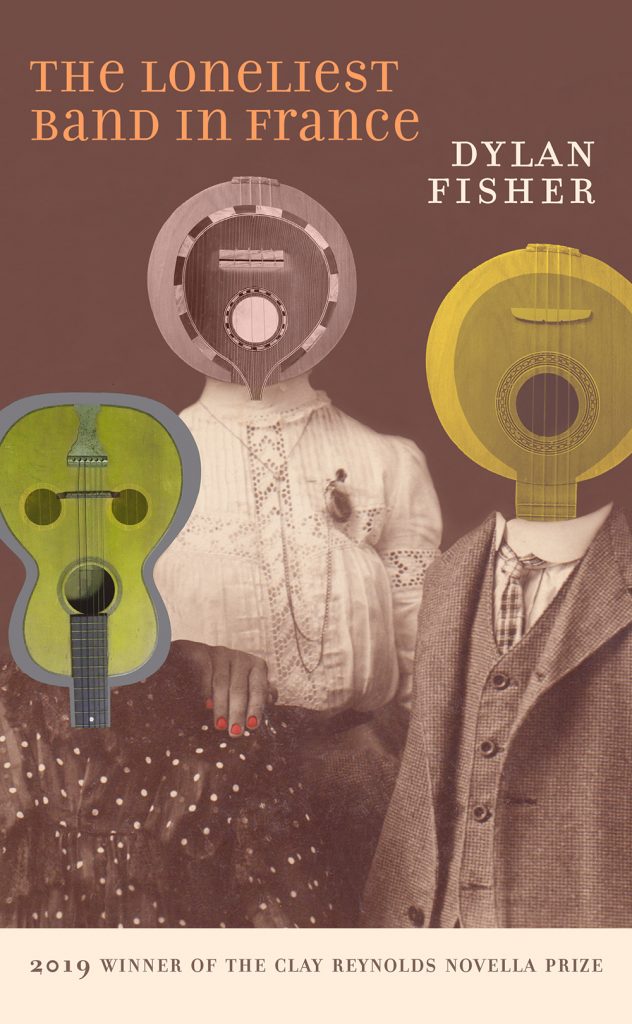

The Loneliest Band in France: A Novella by Dylan Fisher, published by Texas Review Press is presented in halves. In the first, the reader follows Sri Lankan Migara de Silva through the streets of Montpelier, where he is studying at the local university. A stream of occurrences flow into one another, buoyed by a stream of consciousness narration. In the second half, Migara’s father, whose plans and intentions are at the forefront of the first half, shoulders some of the narrative burdens and transports the reader with a series of illuminating flashbacks into the main character’s childhood. It’s a challenge to summarize this work without divulging key points that are best discovered as the author intended.

The Loneliest Band in France: A Novella by Dylan Fisher, published by Texas Review Press is presented in halves. In the first, the reader follows Sri Lankan Migara de Silva through the streets of Montpelier, where he is studying at the local university. A stream of occurrences flow into one another, buoyed by a stream of consciousness narration. In the second half, Migara’s father, whose plans and intentions are at the forefront of the first half, shoulders some of the narrative burdens and transports the reader with a series of illuminating flashbacks into the main character’s childhood. It’s a challenge to summarize this work without divulging key points that are best discovered as the author intended.

It’s revealed early in the text that the title, The Loneliest Band in France is in fact the name of a band Migara—or Paul as he is known to the band members—befriends in the first portion of the novella. Indeed the band is a vital piece of Migara’s tale, but it’s the loneliest qualifier which introduces the reader to one of the prevalent themes coursing through Fisher’s captivating debut.

“…but I did have a title, am human and thus named, have a name, had one at the time, Migara, Migara, Migara de Silva, but instead I gave them a false one, one that was not mine, Paul, a name that allowed me to hide, to blend in despite my darker skin, despite my terrible French, in this country that was so nostalgic and numb…” (6)

The juxtaposition of loneliness in an immigrant versus a native, and later in the work, a child versus a parent creates relief topography of the universally relatable emotion.

Fisher draws a first-person literary narrative, shaded by magical realism and etched with a voice reminiscent of mid-century classics such as Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. The work seems to be the spiritual descendant, particularly as it relates to pacing and experimental nature, of the writings of Mario Vargas Llosa and Jorge Luis Borges. A single sentence makes up 38 pages of the 61-page novella. The author builds dense momentum within comas and ellipses adopting—among other stylistic tools—anaphora, and anadiplosis. Illustrated to great effect within the following quote in reference to Migara’s father.

“…yes, he would want that, would want anything, he would want me anywhere, anywhere but here, for here (in the practice space of The Loneliest Band in France AKA Sirens!) was uncertainty, here was trouble, here was where he might lose his only son, here lay the potential for harm, for death, here neither he nor I could predict the future, spawning outward, minutes or years ahead, although it was already becoming clear…” (4)

This format is unforgiving of a reader with waning or wondering attention. A sharp focus must be maintained for each phrase, each word, each punctuation carries meaning and purpose. The reader risks losing crucial fabric scraps of information, which when sewn together form an examination of rebellion, expectations, existential angst, paranoia, and racism.

Fisher bolsters these interrogations of the human condition with inventive descriptions and analogies. He twists words into fully realized images, transmitting the mesmerizing details from the page into the mind with a fast flourish.

“…two silent children, children I had never heard make a sound, like two gigantic mice, like two cotton balls, just as white, sliding about the tile floors…” (4)

“…if only to gander at the water, the sun bouncing off of it as if the grand attraction in a house of mirrors, reckless and distorted and never the same from one look to the next…” (44)

These contortions of language become a welcome respite. They give the reader a place to rest and refresh, like a ship docking at the port before departing on another journey through rough and exciting seas. The seas of course being the rapid-fire plot turns, shifts in thematic scope, and sudden deep dives into weighty topics.

The author is adept at devising and excavating the confluence of past and future and then returning to the present. All done seamlessly, though not effortlessly. The reader is first introduced to this skill when directions to the bathroom from one of the band members, turn into introspection, and a merciless plummet into the depths of suicide. This technique surfaces a second time when Migara describes his father’s eyes and takes the reader on a protracted journey through time, tense, politics, colonialism, bureaucracy, and familial relationships. At the heart of this novella is a father/son relationship, soured by trauma and presumption.

This is an ambitious work of fiction, making the most of its short format, exploring pain inflicted willingly and unwillingly in the quest for happiness, forgiveness, and change. It is likely to spark much discussion and reflection from readers, not only for its literary merit but also for the portrayal of suicide, along with the ability of a white-presenting author writing from the perspective of a person of color. As one of the marks of excellence in a work of art is the quality of conversation it will generate, the conversations to be generated by The Loneliest Band in France are the worthwhile payoff of reading this novella.

The Loneliest Band in France | Dylan Fisher

Texas Review Press, 2020 | 70 pages

Click here to purchase

We are now open for our Spring 2021 print issue: As Seen on TV. The theme is open to each author’s interpretation, and we encourage creative approaches. As COVID-19 continues to impact our lives, many of us have turned to television as a source of comfort. Yet, these familiar shows are now populated by characters and situations that seem at odds with our current conditions of face-masks, social distancing, and the looming threat to our health. Our lives have become stranger than fiction.

We are interested in your essays, poems, and stories that capture this strangeness. Tell us your thoughts about television as culture, as medium, as entertainment, as sales pitch, or maybe as a source for change… Consider us your captive audience. We look forward to channeling the zeitgeist to interrogate our times. Can’t wait to read you!

“Thespians!” he shouts at us from the front of the crowded restaurant.

Katie and I had been talking to the man ten minutes earlier at the bar. In his fifties or sixties, he wore Buddy Holly glasses and a wide Cheshire Cat smile.

He’d ordered a couple of drinks, and while he waited we made small talk: he asking if we were locals, and we asking how someone from New Zealand—obvious from his accent—had ended up in this small college town. He was here for his daughter’s graduation.

I had taken a sip of my gimlet and smiled happily, nuzzling into Katie’s curls.

“Oh!” the man yelped. “You’re lesbians! How wonderful.”

There was no irony in his voice, just genuine surprise and pleasure. Then: “I have a story for you about my daughter.”

“Okay,” I said, motioning for him to go on.

“One day she was pitching a fit and acting so dramatic.” The man mimicked her, arms akimbo. “So I said to her, ‘You’re quite the thespian.’ And you know what she says?”

We shook our heads no.

“‘What’s that? A lesbian with a lisp?’”

He guffawed, almost spilling his drink, and we all laughed. The joke didn’t seem mean-spirited—more just clever word play from this wild, gregarious Kiwi. We talked with him for a few more minutes, and then he went back to the front of the restaurant where his wife was waiting.

But now:

“Thespians!” the man is hollering down the bar. “Come sit with us!” He’s smiling, waving his arms above his head like an airplane marshal.

One of the bartenders looks up, concerned.

“Are you two all right?”

“Yes, we were just—“

“Is that man harassing you?”

“No, no,” I say, trying to explain.

“I can kick him out,” another one says, wiping his hands on a towel and glaring at the man.

“He was just, um. He’s fine.” We scramble over to the man and his wife, now seated at a booth. They ask us to join them for dinner, and we thank them for the offer, but decline.

When the place has quieted down, the staff huddles around us. We’re regulars and have gotten to know the restaurant owner’s son, Antonio Jr. His boyfriend comes around sometimes, a good-looking blonde with a tan who sometimes helps seat customers. I wonder how Antonio Senior feels about his son being gay. I wonder if the Italian machismo made it worse, and then I think how so many cultures have a sense of machismo, only sometimes there isn’t such a tidy word for it.

A young bartender with a goatee brings us a round of drinks. He tells us his sister is a lesbian.

“I almost lost my shit,” he tells us. “I thought that man was yelling, ‘LESBIANS!’” We laugh for a while at this ridiculous misunderstanding. But then we’re all a little quiet because I suppose he kind of was, though.

***

Katie and I walk into the warm summer night. Eucalyptus trees tall as buildings sway in the wind, long dry leaves crackling in the breeze. We live in a town near the coast, one that on weekends is flooded with farm bros from the Central Valley. Having grown up in LA, I’d never seen anyone wearing a cowboy hat that wasn’t a part of a Halloween costume, but here it’s common to see them, almost always accompanied by a pair of Wranglers.

There isn’t a gay bar in town, no rainbow flags in storefront windows. No businesses owned by gay or lesbian couples, at least not that we know of. But next month, there will be a pride party in the plaza, where young parents will bring their children for the afternoon and let them run around with face paint and glitter.

Still, it’s 2016 in California and we feel comfortable enough holding hands on the street. Some people hardly give us a second glance, but other times we get slight nods of the head, as if to say, You go, girls. I’m surprised that it’s often middle-aged women who give us these shy smiles of encouragement. Once when we were in the definitely-flirting-but-still-just-friends stage of things, a couple of women in mom jeans eyed us from the table next to us. “You two are so cute!” they squealed. We blushed and told them we weren’t together, which was true, though not for long.

But of course, as two women in a relationship, we’re often sexualized by men—straight white men, to be more exact. Once while we’re at the new brewpub in town, eating dinner at the bar, an older man slinks up behind us. Salt and pepper hair slicked back, barking out his drink order. He’s visiting his daughter at college, he tells us, standing too close. His drink arrives, but he lingers, ogling our intimacy. He chuckles to himself and we know that something foul is going to come out of his mouth.

“We all have something in common,” he says. “We all love vaginas.”

And there it is, just out there like the smell of a harsh cologne. A complete stranger talking about our genitals while we’re trying to enjoy our flatbread pizza. And now he’s saying something about how he’d recently divorced and has been dating a ton and how much he loves all the different lips, the pink lips and the brown ones, and I’m not even listening; I’m just looking wide-eyed at Katie and at the people around us: Are you hearing this?

“My daughter likes to ride horses, and I built her this beautiful stable,” he’s saying. How had he switched from vaginas to his daughter’s hobbies?

That’s when a young girl who looks about sixteen, who’d been standing a few feet away with her boyfriend this whole time, approaches. She rolls her eyes so hard I can see the whites and nothing else. She says nothing to us, but tugs on her father’s sleeve until he finally raises his glass and follows.

***

I see a post on Twitter the other day about a twenty-five-year-old who just came out as non-binary to their ninety-year-old grandmother. Expecting her to have the same negative reaction their parents had, they’re surprised when Grandma takes it in stride, saying, “I get it. You’re somewhere in between.”

Then there are Katie’s friends from water aerobics class, most of them in their seventies. Nancy, seventy-five years old, uses the word “partner” for her husband because she wants to use a non-gendered term, plus she’s never really much felt like a “wife.” Alice, sixty-eight years old, accidentally asks about Katie’s husband, but then immediately corrects herself—“partner, I mean.” There’s Gene, seventy years old, happily married and off to Mexico for the winters with his husband and Sheryl, who lost her wife of thirty years not too long ago.

So when I catch myself or others using “It’s a generational thing” as an excuse for homophobia, I think of the white-haired water-loving, people-loving septuagenarians at Evergreen Wellness, who remind me to expect more of people, no matter their age.

One time when Katie and I are on vacation in Portland, a Lyft driver picks us up in a minivan. It’s summer, and the driver, a man in his late sixties, has the windows rolled down to let the breeze in. He has a Jerry Garcia vibe, with a mustache and tan arms, his left one three shades darker than his right. We chat for a few minutes, and upon realizing we are girlfriend and girlfriend, the man opens up and tells us his story.

“My daughter’s best friend growing up came out to his parents in high school,” he starts, leaning back into his seat. “They kicked him out.”

“Oh no,” we murmur in the back seat. Heavy, hot air billows in through the windows, but it feels good on my skin, chilled from an afternoon of hopping around air-conditioned coffee shops.

The man continues: his daughter’s friend came to live with them and eventually, the man and his wife adopted him.

“That’s wonderful,” we say.

“And now Michael is married and transitioning.” It takes Katie and I a moment to realize that this whole time, the man has been using Michael’s preferred pronouns. The realization makes my heart swell and feels like the opposite of everything that’s been going on in the world.

“Everybody says we’re so tolerant,” he tells us, making a wide turn. “Tolerance is fine, but in Portland, we embrace.”

Katie and I smile at each other through teary eyes. The van gently bounces over a speed bump, and I’ve never felt lighter before.

Author Bio: Kristin Ito is a writer living in Portland, Oregon. Her essay “The Quiet” was nominated by Hypertext Magazine for The Best American Essays, and her work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review, WhiskeyPaper, and other publications.

Author Bio: Kristin Ito is a writer living in Portland, Oregon. Her essay “The Quiet” was nominated by Hypertext Magazine for The Best American Essays, and her work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review, WhiskeyPaper, and other publications.

Website: kristinito.com

Twitter: @kristin_kimie

They say the uterus is the thing that holds a woman inside of herself. Blood-wetted. Always emptying or filling. A tide on the open ocean. Entangled. Drumming heartbeats. Blankets of blood thickness. Umbilical cord wrapping around and around and into us. This piece we hold internally, forking toward the tiny livers and the tiny hearts, it grows us, feeds into what will be closed and is now our open mouth, our open nose, our open wound. I wonder what happens to that six inches of circuitry that tethered us, hearts to bellies, once we have been cut into our own bodies.

I look for the answer in a book written in 1971 by a white man with an eye patch. He blames women for their own pain. He doesn’t have the answer.

I look for the answer in my friend training to be a midwife. She pulls a pelvis and a doll out of her purse. Dances it through bone, the head only fitting one way, the baby working its way out like a thing that multiplies. She says her favorite part of a birth is the few seconds where the mother has two heads. I want to ask her what the sound is like. Which head is screaming. Instead I ask her to have my baby. I ask her umbilical questions. She doesn’t know the answer but will get back to me.

Have you ever seen a time-lapse picture of a birth? How flesh you thought you understood will unfold and unfold again, its purpose clear, the head crowning monstrously and pulling the halves of the pelvis open. Because really the head doesn’t fit, and what you thought was one bone might be two, stretching open, and in the picture the head is more woman than the skin around it that is tearing. It doesn’t look like it, but they are working together to move apart.

I find the answer on Wikipedia but don’t trust what the internet is saying. That it just dissolves into fibers. Was once vital and is now umbilical trash, wedged in the corners of our cavities, bothering organs or becoming a part of them, slowly sifting its way out of our container. I want it to integrate, become the hot core of us, the thing that tells where our depths end and turn into liquid. I want the real answer. I want to hear it from the open lips of a mother or a beautiful dentist or the belly of my sister.

I become fascinated by the placenta. The thick meat of it. The grey and yellow and blue of it. Mother’s resources going in, baby’s waste going out, vein filled, arterial. How the blood circulates but doesn’t mix, conversing from arm’s distance. How it connects them, so helpfully, until it falls into the hands of the mother or the midwife in that last push and is useless. My mother’s gynecologist keeps a polaroid of our placenta in her desk drawer and every year for a decade while my mom is lying face up in paper clothing, she takes us into her office and makes us look at it. The biggest one she has ever seen. We are famous for what was built in the space between us, our needs gigantic, our mother tiny and beach-balled by our unfurling.

There is another picture of the same placenta in a book we have to read every birthday. Spread flat on a hospital table, part steak and part brain, knotted tendrils. The story is it got put in the freezer until they figured out what to do with it and then the fridge died and it was moved to a cooler on the back deck, maybe a heat wave, and after that nobody remembers.

My mother writes letters at the kitchen table and four blocks away her mother writes letters at the kitchen table. The thing that connects them is old and beginning to harden. She sends the letters out towards us haunted by her ghosts by our tethers. Missed calls, early morning messages, I can feel her tugging.

I can feel the stem in me, the belly button ending and the knot of muscles and deeper than that, a forking or a fracturing. It touches organs, wraps around the stomach and up the throat, speaks for me without language, urges me to find strangers to touch, whispers up at me in the milky darkness: do you miss me, it says. Then the mother’s voice, face to the ocean, calls: come back to me. I need to try again to make you whole and clean and uncomplaining. The placenta flexes in the night. We drop back into the ocean like we’ve always wanted.

Author Bio: Oona Robertson is a writer and furniture maker based in Western Massachusetts.

Instagram: @newspine

Family dinner.

Suddenly, at the dinner table, she stops eating. First a bend at the neck, then head, a leadening. The body always follows. Her fork skids into the depths of bare feet, her torso long and stretching sideways. It is almost imperceptible, the slow fall and then she is dangled, her head a few inches off the ground. The solid weight of her hips still seated. The fingers curved like a dead animal. One hand pressed watch-face to combed carpet. It beeps once, marking the end of an hour. Then silence. All eyes pointing forward except the mom, who blinks once, sliding them up and then back into place before opening. Clack of knife hitting the butter dish. Throat sounds. A napkin dropped and not recovered. The table is dark wood, room of ominous paintings. A few chairs unfilled. A coldness like occupation. Thick draft of collective breath, smell of under-cooked meat and distance. Her hair brushes the floor to the rhythm of her cerebral spinal fluid. The mother asks to be excused from the table.

Dollhouse.

She shook the doll with an old vengeance. Listening was no longer enough. The doll would sit slumped against various furniture and she would cry and point and rave. It was nice to have a place to put her anger. The doll didn’t mind, or did nothing to stop it. Its face was beautiful and satisfying to prey on. Often she would get so angry a hardness would rear up in her and she’d want to throw the doll off the roof of their house or squish its beautiful fucking face under the heal of her Mary Janes, the nose breaking off like porcelain. She hated what she could see about herself in the other dolls’ forced-open eyes. The nose stayed in one piece like the lost part of some old statue. She thought of the people who owned them patching it back on with the soft tip of a brush dipped in superglue, and her anger mounted. She stomped around the house slamming cabinets in the fake kitchen and the door of the cast iron oven so fucking lifelike you could light a fire with broken-in-half matches and cook if you could find an egg small enough. When her anger got so big the people noticed, they would pull her up to their scary mouths by the buckle of her overalls and yell in some garbled language, shaking her from tip to top. This made her extremely nauseous, and to punish them she would walk past the pretend toilet and kneel on the living room rug, heaving stale air from her hollow body.

Breakfast.

The egg is put down in front of her. The table is farmhouse. Her palms are wide and white. She cracks the shell like her mama taught, with the edge of her spoon and the tink of good intentions. The inside is still embryonic, goo of wet turned coagulate. She has to eat it. Each time she sets down her spoon she is given another, slightly bigger, until they don’t fit in the cup and she has to hold them in the palm of her hand. She was not hungry to begin with. The shells start to resemble cracked skulls. The yolk is an eye or a uterus. The white part is blinding and she can feel something sticky crawling down her fingers, same as her tongue is coated. The pile of shells on the table grows and she can smell newborns and the field outside. The one window gets greener and then starts to oscillate and the eggs clack around in her head which is now also an egg and she no longer sees the problem.

Author Bio: Oona Robertson is a writer and furniture maker based in Western Massachusetts.

Instagram: @newspine

Editor-in-Chief Areej Quraishi

Managing Editor Benjamin Stallings

Engagement & Design Editor Lindsay Olson

Fiction Editors Tanya Shirazi & Xueyi Zhou

Nonfiction Editor Dominque Conway

Poetry Editor John B. Oldenborg

Editorial Assistant Charlie Bartlett

Contributing Editors Henry Gunderson, Anne Livingston, Cecil Lycoris, Leah Mell, Marlan Smith, Kelly Stith, Carlos Tkacz, Jo Wallace

Readers Justine Baker, Carrie Bindschadler, Nicholas Bon, Sara Brown, Alycia Calvert, Delight Ejiaka, Benjamin Favero, Jordan Foster, Eli Jacobs, Arel Wiederholt Kassar, Veronica Klash, Clarissa Leon, Alice Letowt, Aeriel Marillat, Nicole Minton, Destiny Pinder-Buckley, Avery Portis, Sara Tausendfreund, Layhannara Tep, Tonya Todd, Rachel Walker, Kailee Wingo

We support, uplift and publish Trans voices. In today’s U.S. climate of anti-trans rhetoric and policy, and the killing of trans bodies and minds, it is imperative that as a literary magazine, we commit to publishing a global range of trans writers, with no attempt at policing what trans looks and sounds like. We respect people on the trans spectrum and seek to be a safe place for trans thinkers and trans stories.

Consider donating to the following causes:

Transgender Law Center

The Okra Project

Emergency Release

Marshap

We stand together with the Black community and commit to double down on anti-racist efforts. We continue our mission to amplify extraordinary voices, feature writers from every part of the globe and add to the conversations surrounding oppression, prejudice, fear, and raw honesty.

As ever, as always, and forever, Black lives matter.

We remember: Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, George Floyd, Atatiana Jefferson, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor

We remember the victims in Las Vegas: Tashii Brown, Keith Childress, Trevon Cole, Sharmel Edwards, Stanley Gibson, Junior Lopez, Roy Anthony Scott, Bryon Lee Williams, Rex Wilson

We hold space for the numerous other Black people whose names did not enter the public record, or whose lives have been lost to the archive.

Already a subscriber? Like what we do and want to send a little love? We accept bribes tips!

Thank you for your continued support of our little magazine.

Can you get a Witness?

Why, yes. Yes you can.

Become one of our members to subscribe to two years of everything we make. You’ll receive our themed, print issues as well as our capsule/zine issues!

Visit our online shop to get started with a membership, or to order individual issues.

Looking for a specific issue or back issues from the vault? Contact us via email and we will make sure to oblige!

Editor-in-chief Jarret Keene & Emily Setina

Managing & Engagement Editor Lindsay Olson

Fiction Editor Wendy Wimmer

Assistant Fiction Editor Robert Ren

Nonfiction Editor Cody Gambino

Poetry Editor Lindsay Olson

Readers Anthony Farris, Dylan Fisher, Ruth Larmore, Kathryn McKenzie, Chantelle Mitchell, Flavia Stefani, Jordan Sutlive, Ariana Turiansky, Alexandra Murphy, Bronwyn Scott-McCharen, Carrieann Cahall, Ilanit Moskul, Jo Hahn, Marycourtney Ning, Sanjana Gothi, Sarah Spaulding

Editor-in-Chief Emily Setina

Managing & Engagement Editor Lindsay Olson

Fiction Editor Robert Ren

Assistant Fiction Editor Areej Quraishi

Nonfiction Editor Cody Gambino

Poetry Editor Heather Lang-Cassera

Readers Alexis Noel Brooks, Alycia Calvert, Benjamin Stallings, Chelsi Sayti, Claire Mullen, Dylan Cloud, Erin Turner, Flavia Stefani Resende, Jennifer Quintanilla, Jeremy Freeman, Jesse Motte, John Oldenborg, Jonquil Harris, Jordan Sutlive, Justine Baker, Kelly Lindell, Lynda Montgomery, Mir Arif, Percy Kerry, Sara Guiang, Sara Tausendfreund, Sarah Spaulding, Stephanie O’Brien, Stephen Ira, Steven Aiken, Talia Aharoni, Tonya Todd, Vandana Sehrawat, Veronica Klash, Win Frederick

Editor-in-Chief Emily Setina

Managing Editor Christina Berke

Engagement Editor Lindsay Olson

Fiction Editor Robert Ren

Assistant Fiction Editor Areej Quraishi

Nonfiction Editor Cody Gambino

Poetry Editor Andrew Collard

Readers Erika Abad, Steven Aiken, Mir Arif, Justine Baker, Alexis Noel Brooks, Soni Brown, Alycia Calvert, Cristina Cisneros, Dylan Cloud, Emily Daniel, Win Frederick, Sara Guiang, Stephen Ira, Eli Jacobs, Veronica Klash, Kelly Lindell, Lynda Montgomery, Jesse Motte, Stephanie O’Brien, John Oldenborg, Jennifer Quintanilla, Mark Ranchez, Flavia Stefani Resende, Chelsi Sayti, Vandana Sehrawat, Sarah Spaulding, Benjamin Stallings, Jordan Sutlive, Sara Tausendfreund, Tonya Todd, Erin Turner

Editor Robert Ren

Managing Editor Christina Berke

Engagement & Design Editor Lindsay Olson

Fiction Editor Areej Quraishi

Nonfiction Editor Mir Arif

Poetry Editor Jo O’Lone-Hahn

Editorial Assistant Oona Robertson

Contributing Editors Alycia Calvert, Emma Hardy, Henry Gunderson, Eli Jacobs, Nicole Minton, Ezra Noel, John Oldenborg, Jennifer Quintanilla, Amanda Santana, Marlan Smith, Ben Socolofsky, Sarah Spaulding, Sara Tausendfreund, Olivia Williams, Sara Guiang

Readers Erika Abad, Justine Baker, Charlie Bartlett, Alexis Noel Brooks, Veronica Klash, Alice Letowt, Laurel Miram, Jesse Motte, Mark Ranchez, Benjamin Stallings, Vandana Sehrawat, Tonya Todd

Faculty Advisor Maile Chapman